He liked the trappings of being a pro athlete, but he wasn’t willing to put in the work. For instance, he didn’t eat or sleep properly.

Jamie Watson had a bold and bodacious dream.

“I wanted to be a synonymous name in soccer,” Watson says.

Yet Watson didn’t appreciate each significant step along the journey because he was too singularly focused on the ultimate goal.

And he didn’t get there.

Nearly two years after retiring, the 32-year-old doesn’t have any regrets, enjoying his family and his job as an on-field reporter for Minnesota United FC. In early November, at the club’s corporate office in Golden Valley, Minnesota, Watson greets staffers — from interns to the general manager — with joy and enthusiastically highlights the team’s future, which includes the opening of Allianz Field in St. Paul next March.

“If I could do it all over again,” Watson says, “I think I would pick my head up a little more and look around, and realize how fortunate I was.”

Now he does.

Jamie Watson is one of a few players to score in all four divisions of U.S. soccer. Getty Images

LATE BLOOMER

Watson grew up in Arlington, Texas, with his parents and twin brothers, who are 22 months older. One of them, Brett, has cerebral palsy.

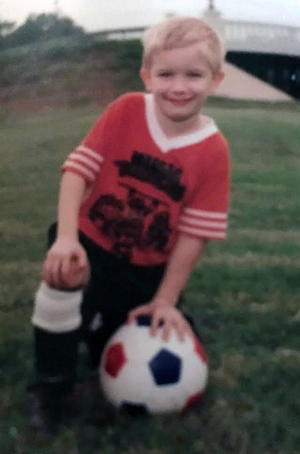

No one in Watson’s family played soccer, but his parents liked that five-year-old Jamie seemed to have fun playing for the Ninja Turtles of the Coppell Youth Soccer Association.

“They took me to every practice,” Watson says. “They are the reason I got to this point. For that, I’ll forever be grateful. It changed my whole life.”

Before kickoff, the boys would yell, “Cowabunga!” Watson showed enough skill that his coach asked for his autograph.

“He said, ‘One day, you’re going to be famous,’ ” Watson recalls.

But Watson wasn’t an immediate star.

At 13, he tried out for the Olympic Development Program. He made the C squad, the third-best of three.

But Watson loved the sport, and he committed himself to improving.

“My mom always said, ‘You never know who’s watching,’ ” Watson says.

Then he started bounding up stairs toward his goal.

5-year-old Jamie Watson. Courtesy photo

He starred for a north Texas team at a regional camp in Alabama, where he was the top goal-scorer. At a tournament in Costa Rica, Watson caught the eye of a national team coach. During his sophomore year in high school, Watson received a life-changing phone call. IMG Academy wanted him to move to Florida and train there.

He’ll never forget what his parents asked him.

“Is this what you want to do with your life?”

Now a father, Watson is overwhelmed even more by what his parents did.

“It was tough for them to let me make that decision,” Watson says. “They were basically giving up their kid.”

RISE AND FALL

Watson’s game improved, and he landed a scholarship to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He was the ACC Rookie of the Year, and he was named to the Top Drawer Soccer’s All-Freshman Team.

In his second season, he made the ACC All-Tournament team and All-ACC team. In two seasons, he scored 12 goals and had 10 assists.

But Watson had blinders on. He didn’t celebrate his ascension.

“In college, I didn’t enjoy it,” Watson says. “I wasted a year and a half at one of the best schools ever.”

Watson barely attended classes, he didn’t invest in relationships.

He then signed a Generation Adidas contract with Major League Soccer. He was selected 13th overall in the first round of the 2005 MLS SuperDraft by Real Salt Lake. Not old enough to legally drink, Watson purchased a house and a fancy SUV.

Watson’s big dream seemed within arm’s length.

“I get to the top, and I thought, ‘I’m there,’ ” Watson says. “But I forgot there are others trying to get to that spot. There’s a fine line between confident and cocky, and I was over the line.”

There’s a fine line between confident and cocky, and I was over the line.

– Jamie Watson

His success was fleeting. He liked the trappings of being a pro athlete, but he wasn’t willing to put in the work. For instance, he didn’t eat or sleep properly. Many players were off-put by Watson, but not veteran Brian Dunseth.

“You see a kid walking through the training room door, with two brand new Adidas boots, a little cocky goal scorer coming out of the U.S. system,” Dunseth says. “We saw a cockiness and a swagger that maybe didn’t deserve to be there, per se. But at the same time, it was a new generation of young players with a lot of high hopes riding on their shoulders.

“In that moment I thought, ‘I like this kid.’ ”

He made 39 first-team appearances at Real Salt Lake, but he had only two goals and one assist. On January 22, 2008, Watson was waived by the club.

Everything changed in a heartbeat.

Four months later, Watson surrendered his professional status so he could play in the Premier Development League, collecting unemployment checks and sleeping on a couch in a two-bedroom apartment occupied by four other roommates.

“That was rock bottom for me,” Watson says. “Something wasn’t working, and it wasn’t everyone else. It was me.”

But he refused to give up.

RIGHT APPROACH

Watson re-discovered a newfound passion for soccer.

“The only way to go was up,” he says.

There were more challenges ahead, bouncing among multiple states in lower-tier leagues. After a single appearance with FC Dallas in 2008, Watson headed to the Wilmington (North Carolina) Hammerheads, where he won the USL-2 scoring title and MVP award.

He then signed a two-year USL-1 contract with the Austin Aztex, where he continued his strong play, before he got another important call, this time from Adrian Heath.

Heath had taken over at Orlando City of the USL Pro division. He knew all about Watson’s story.

“Jamie was one of the early homegrown in the league,” Heath says, “among those that thought he made it long, long before he actually had.

“The unfortunate thing about football, it’s a great equalizer. The minute you take your eye off the ball, before you know it, you can be out of the comfort zone you were in.”

Heath, though, noticed Watson’s more humble, hard-working approach. Watson embraced and excelled in Heath’s system. It was a monumental move in his resurgence.

“It’s hand in glove,” Heath says. “The more you buy into the team concept, the better you do as an individual.”

THREE LIFE LESSONS JAMIE WATSON LEARNED IN HIS SOCCER CAREER

Watson played the best ball of his career. In 60 appearances, Watson scored 23 goals, helping the team win a regular-season title and league championship. Just as important, thanks to the steady influence of Dunseth, Watson continued to excel off the field. He was popular with the media, and he was a go-to for community service opportunities.

“He became an important cog in what we were doing,” Heath says. “It’s like a fine wrist watch. It takes all those parts to make it work. When I look at that group, they are the guys who got that club from being a small, minor-league team to what they are now in the MLS. It wasn’t just what they did on the field. They were tremendous ambassadors off the field.”

Orlando City joined the MLS before the 2015 season.

By then, though, Watson had signed with Minnesota United FC, another upstart club searching for an identity. Early in 2015, Watson felt like he was in the best condition of his life. But on a routine play, along the sideline, he was shoulder-to-shoulder with an opponent when his knee buckled.

He crumpled, and he immediately realized he’d suffered a major injury.

“It was less about the pain,” he says of the torn ACL, “I felt God had this happen for a reason.”

After surgery, Watson needed his wife’s help to even put his leg in the car for a month. The rehab was a long one, requiring a full year. But he had a new motivation: His children.

On Sept. 17, 2016, shortly after the birth of his son, Watson returned to the field at the National Sports Center in Blaine, Minnesota. It marked an important step in his career. Then, in the 30th minute against the Ottawa Fury, Watson scored a goal, and he pointed skyward.

That was one of the highlights of his career — and he enjoyed every moment.

Two months later, heading into United’s debut MLS season, Watson welcomed a familiar face; the club hired Heath.

STICKING AROUND

Watson retired in January 2017, finishing with a unique distinction that sums up his fascinating career. He is one of a few players to score in all four divisions of U.S. soccer.

“I’m proud of how I worked my way back up through the system,” Watson wrote on the blog Fifty Five One. “I always said I wanted to make it back into MLS.”

Brad Baker, formerly United’s director then vice president of broadcasting, invited Watson to audition for a spot on club’s television crew. At the time, though, Watson also had three NASL teams interested in signing him to continue his playing career.

“If I was single, I would have kept playing, maybe three to five more years,” Watson says. “But I was 31, (coming) off of an ACL tear, a wife with two kids. Did we want to keep moving, especially since we loved it here?”

Watson consulted his mentor Dunseth and followed in his footsteps, transitioning from player to broadcaster. He prides himself on his preparation, always diligently doing his research to make sure he is knowledgeable about United as well as its opponent. He also brings energy and empathy to his role.

“He can ask questions that people want but also knows there are certain roads we won’t go down because it can open up a can of worms,” Heath says. “He’s very sensible. The fact that he’s been a player, he knows how it works and what he can and can’t do.”

Watson is excited for his third season with his two broadcasting partners, Callum Williams and Kyndra de St. Aubin.

“All three of us are excited to see how this (new) stadium can help transform this club,” Watson says. “When you have the stadium, it sets you in a different class. What that does to the confidence to the club — both on the field and off the field — gives you a massive sense of pride.”

Given their extensive relationship, Heath likes many things about Watson. But asked to share his favorite memory, Heath recalls something that happened off the pitch when they were together at Orlando City.

“We brought in eight or nine children in wheelchairs, and Jamie was just so natural, and he was able to interact with them and make them feel a part of the group,” Heath says. “They gravitated toward him because of his experience with his brother. It was incredible to see. That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen Jamie do.”

That was something that concerned Jamie about the end of his playing career; he thought he would lose his platform to be able to help others and support organizations like the Special Olympics.

“I’m glad that I was able to experience a life where I had a brother with cerebral palsy. It taught me to be patient, and kind and loving,” Watson says. “Then God blessed me with this ability — because I was a soccer player — to impact people like my brother.”

“I know the impact that people who volunteered to help my brother had on him and my family, so I want to do that with other people with special needs.”

Dunseth and Watson still talk regularly, and the mentor is proud of his mentee. They have shared the lows and highs together.

“I’m humbled that he looked at what I’d been doing,” Dunseth says, “but he also has figured out his own path. I really like his style. … It’s been fun to watch Jamie develop into the man he is today.”