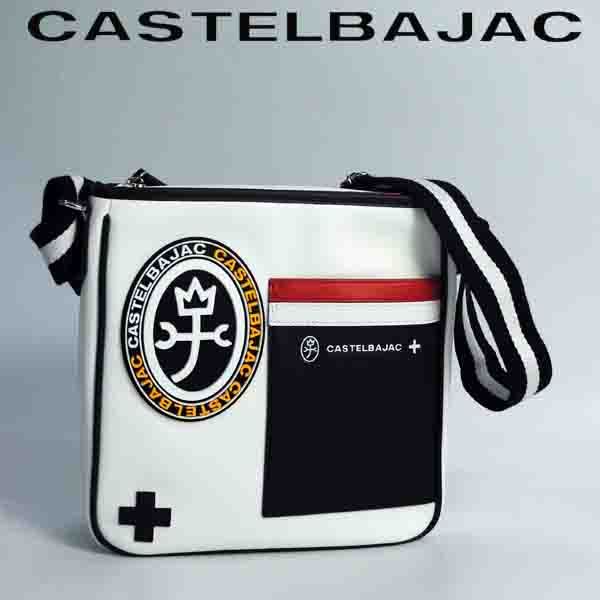

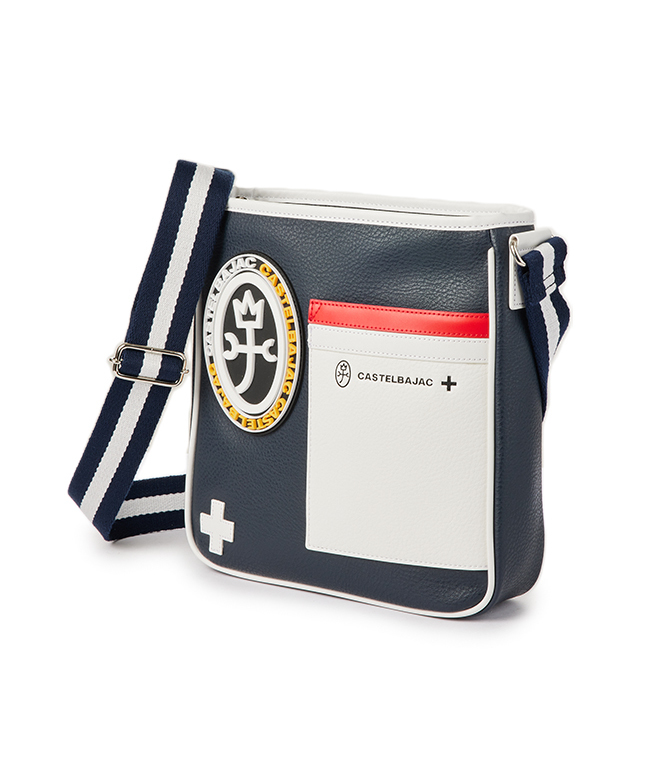

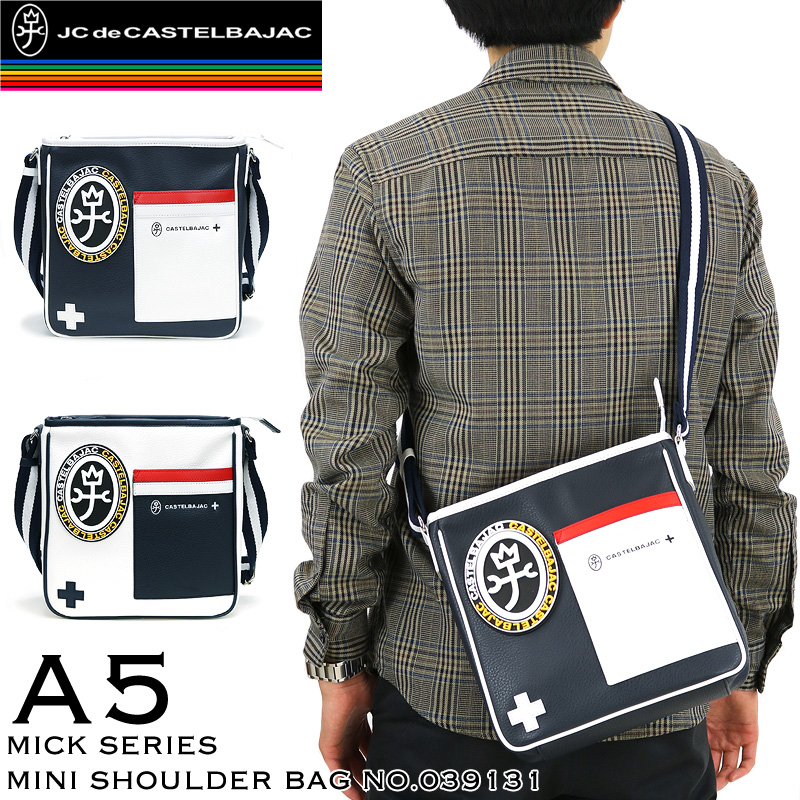

カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ 039131 ホワイト

(税込) 送料込み

商品の説明

こちらから私の出品している

カステルバジャックの商品が確認できます

↓ ↓ ↓

#いぬのカステルバジャック出品

ブランド名:CASTELBAJAC / カステルバジャック

商品名:ミック ショルダーバッグ

商品コード:039131

サイズ:幅23cm×高さ25cm×マチ6cm

色:ホワイト

品物の状態■正規ライセンス品■新品■

素材:ポリウレタン×ポリ塩化ビニル

仕様:本体素材には、ナチュラルシボ調の型押しを施したソフト合皮を使用。

ロゴマークは厚みを持たせた特大サイズのラバーを使用しインパクトを。

トリコロールカラーを大胆に配し、タウンからゴルフ等のレジャーシーンにも合うシリーズ。

アシンメトリーに配したポケットは、仕様頻度の高いものを収納すると便利にご使用頂けます。

商品についてご不明なことがございましたら、お問い合わせ下さい。

#カステルバジャック

#CASTELBAJAC

#バッグ

#ショルダーバッグ

#トートバッグ

#リュックサック

#メンズファッション

#レディースファッション

#レザー

#キャンバス

#コラボレーション

#デザインバッグ

#ビジネスバッグ

#トラベルバッグ

#スーツケース

#ウエストバッグ

#ボストンバッグ

#クラッチバッグ

#カジュアルバッグ

#フェスバッグ

#小物入れ

#オーガナイザー

#ポーチ

#財布

#キーホルダー商品の情報

| カテゴリー | メンズ > バッグ > ショルダーバッグ |

|---|---|

| ブランド | カステルバジャック |

| 商品の状態 | 新品、未使用 |

カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ 039131 ホワイト-

カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ 039131 ホワイト-

正規品 メンズ レディース カステルバジャック CASTELBAJAC カステル

楽天市場】カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ バッグ ゴルフ メンズ

カステルバジャック ミニショルダー Mick ミック メンズ 039131

カステルバジャック ミニショルダー Mick ミック メンズ 039131 CASTELBAJAC | 肩掛け カバン 合成皮革

CASTELBAJAC カステルバジャック Mick ミック ミニショルダーバッグ

楽天市場】カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ バッグ ゴルフ メンズ

CASTELBAJAC - カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ 039131

カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ 039131 ホワイト-

カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ Mick-ミック 039131 : 039131

楽天市場】カステルバジャック ミニショルダー Mick ミック メンズ

カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ 039132 ホワイト

正規品 メンズ レディース カステルバジャック CASTELBAJAC カステル

楽天市場】カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ バッグ ゴルフ メンズ

ショルダーバッグ小<ミック> | カステルバジャック(CASTELBAJAC

CASTELBAJAC カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ(小) 縦型

カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ メンズ レディース 縦型 縦長

カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ メンズ レディース 縦型 縦長

カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ 039131 ホワイト-

ノベルティ プレゼント 】カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ

![Amazon | [カステルバジャック] ミニショルダーバッグ Mick(ミック](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71PCpF1wxYS._AC_UY300_.jpg)

Amazon | [カステルバジャック] ミニショルダーバッグ Mick(ミック

カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ メンズ レディース 縦型 縦長

CASTELBAJAC(カステルバジャック) ミニショルダーバッグ Mick(ミック

正規品 メンズ レディース カステルバジャック CASTELBAJAC カステル

楽天市場】カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ バッグ ゴルフ メンズ

カステルバジャック) CASTELBAJAC カステルバジャック ミック ワン

CASTELBAJAC カステルバジャック ミック ショルダーバッグ(小) 縦型

カステルバジャック ミニショルダー Mick ミック メンズ 039131

![Amazon | [カステルバジャック] ショルダーバッグ Mick ミック メンズ](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61YcPCpjwTS._AC_SY395_.jpg)

Amazon | [カステルバジャック] ショルダーバッグ Mick ミック メンズ

ノベルティ プレゼント 】カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ

CASTELBAJAC(カステルバジャック) ミニショルダーバッグ Mick(ミック

正規品 メンズ レディース カステルバジャック CASTELBAJAC カステル

ブランドのギフト CASTLBAJAC カステルバジャック ショルダーバック

カステルバジャック ヨット?ミニショルダーバッグ 028161 ホワイト

楽天市場】カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ バッグ ゴルフ メンズ

カステルバジャック ショルダーバッグ Mick-ミック 039131 : 039131

カステルバジャック) CASTELBAJAC カステルバジャック ミック ワン

カステルバジャック ミニショルダー Mick ミック メンズ 039131

カステルバジャック CASTELBAJAC ショルダーバッグ ミック 39131

商品の情報

メルカリ安心への取り組み

お金は事務局に支払われ、評価後に振り込まれます

出品者

スピード発送

この出品者は平均24時間以内に発送しています